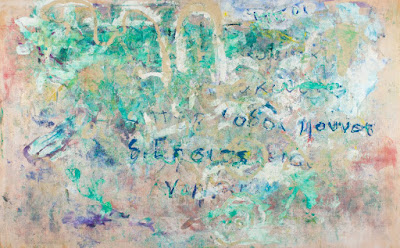

Anne Sherwood Pundyk, "Pitch," 2015, Latex, Acrylic, Colored Pencil and Stitching on Canvas, 86.25 x 91 inches

Painters Hovey Brock and Anne Sherwood Pundyk discuss their painting practices using Kant’s Third Critique and two recent lectures on speculative realism—one by John Searle and the other by

Graham Harman ]—as points of departure.

Hovey Brock: Philosophical

thought is a useful way to frame any kind of practice; all practices are

fundamentally speech acts of one type or another. So, anything that is born out

of a set of conventions, which is what I think painting is, amounts to a very

specific kind of speech act. I am interested in all the social conventions that

support what a painting actually is and I think this has something to do with

non-representational painting.

Anne Sherwood Pundyk : My

attraction to Kant’s ideas on beauty in his Critique

of Aesthetic Judgment is centered on his logical digging down into how it

is we are aware of our own subjective experiences. This and his emphasis on

experiencing art in person are central to my painting: the interconnection of

the subjective voice and the body. Kant gives us permission to attribute weight

and value to the subjective vantage. I gather from the lectures you recommended

about speculative realism that you see a shift away from Kant’s emphasis on

subjectivity.

HB: I selected

the Harman lecture because there is a sense in which the object-oriented ontologies

in Harman’s form of realism hark back to Kant’s division between noumenal and

phenomenal. Specifically because he talks about those things where we can talk

about the object and then there is the object in and of itself, which we can’t

really talk about. I find Harman’s division a little too black and white. I

like Searle’s approach because he is working from the ground up and at some

point we do literally touch on physical objects in the world. I think that

there are ways that we do connect with the thing in and of itself. As a way to

tie these ideas to our paintings, let’s get to some specifics and then we can

bring in the philosophy. Tell me about your technique for making the painting, Wind O. Obviously there is some pouring,

some painting; there is a lot going on here.

Hovey Brock, "Anaxagoras, 2015, " 30" x 48", oil on panel, 2015

THE MONKEY WRENCH

ASP: I want Wind O to create a space for the viewer

where she is the subject. The domain of my painting has shifted outward; I want

the viewer to feel that surge of attention and unconditional love. Like all my most

recent, large paintings, Wind O is on

unstretched, drop-cloth canvas. For me, it evokes a stage backdrop and feels more

direct and authentic than a stretched canvas.

Color drives my compositions, which play back and forth

between fluid, bleeding forms and vertical, zig zagging interventions. I make

large pours, folds and prints with the painting on the floor and move it up on

the wall to locate the geometric elements. For example, I made the bright blue

pour in Wind O and then folded the

canvas to create the central diagonal Rorschach shape. Given the size of the

pieces—7 by 8 feet—this is a full body process and that physical presence can

be felt in the work. I started the piece in the dead of winter when my studio

in Mattituck was surrounded by 4 feet of snow. By the time spring came and I

was able to take the painting outside to work. I created the purple tendrils

that flow across the painting by placing the painting on a sloped area of lawn

and pouring the paint across the surface.

The last element is an architectural reference to a window. It’s not

fully rendered; it’s a degenerated image of an opening that was the basis for the

light grey panel.

HB: Are you

deliberately avoiding any overt references or are there references that I am

missing here?

ASP: I am not

looking for direct representation. I am not running away from it, but I am just

not interested in it. Imagery feels distracting.

HB: Ok. Good.

ASB: I made a

suite of 6 new paintings for a solo show at Christopher Stout Gallery, New York

last spring called, “The Revolution Will Be Painted.” Several of these along

with a new painting are now in, "Unconditional Paint," a solo show at Selena Gallery, LIU

Brooklyn up through October 28th. While I used a consistent formal premise, each painting resolves

itself in a different way. There is something that has to come in from outside

of the parameters of my process in order for the piece to feel finished—let’s

call it a “monkey wrench.” So, for instance, the window element in Wind O is not in the local vocabulary of

the piece, but it needed to be in there.

Anne Sherwood Pundyk, "Wind O," 2015, Latex, Acrylic, Colored Pencil, and Stitching on Canvas, 84.5 x 92.5 inches

HB: My take on

that is that there is something inductive that you are trying to do. You are

trying to bring in something outside the logic of your pictorial thinking that

would allow it to open up in a way that it would not ordinarily.

ASP: Yes, It’s like

a logic pattern: “If it’s not this or that, there will be a third possibility.”

HB: Sure, this reminds me of Gadamer’s hermeneutic

process of reading something and then expanding your horizons based on this

reading. He talks about the horizon as a metaphor for what we are able to

encompass mentally. As you bring in new material you expand your horizon. The hermeneutic

circle is something where you are always going out to the horizon and then back

to the particular and figuring out how the particular works within the greater

horizon. You bring in your monkey wrench, which is a way to continually expand

your horizons.

ASP: That’s

great. I like that. So let’s take a look at your painting, Heraclitus.

THE BACKGROUND

HB: This is a

work that’s painted on a wood panel. I want the wood to show through. Wood is

one of the ancient painting supports originally used. In the title I am

referring to Heraclites, the philosopher, but also as a form of thinking that

operates in the background. Heraclitus’ thinking is agonistic. He is always

talking about the road that leads up is also the road that leads down. He says

that there is something valuable in the very idea of war because conflict

generates something new. “Background” is a term Searle uses that is one part of

the thinking about the process of representation.

As far as the color goes, Heraclitus is interested in the

energy that is created through antagonism. I picked green as a reference to the

natural ways of the world. There is something primitive about the drawing

itself, which is deliberate; Heraclitus’ thinking has a primitive aspect. He is

one of four pre-Socratics I have chosen as subjects where their writings are

all only extant as fragments of copies. The only way we really know them is

from the way other people have interpreted them. I love that they literally form a background

to our thinking that is at this point is obscured. There is so much else in our

approach to thinking, which is obscured. It’s in the background and you can’t fully

recognize what it is. In the sciences, we are finally beginning to have enough

understanding of neuropsychology to get a sense of what the background is. I

also think the background involves certain fundamental physco-social processes

that allow for the construction of representation and the development of meaning.

I am using Heraclites and the other pre-Socratics as metaphors for these

psychosocial fixtures. These fixtures are very important in the formation of

our ability to use these very specific speech acts to create meaning in our

world.

The writing on this painting is from some of Heraclitus’ fragments.

I used the most famous one, which translates as, “Stepping into the same river,

different waters flow.” Another way you could think of it is, “Different strokes

for different folks.” This is a fundamental type of agonistic thinking where your

point of view is not going to be my point of view, but in talking we are going

to arrive at some sort of understanding. For me, I would call that a

psychosocial event that happens in any creation of meaning, right? (Laughs)

ASP: Sure,

exactly.

HB: The fact is that

while we are sitting here having this conversation we are creating meaning.

It’s very agonistic in that you have your point of view and I have my point of

view. As the result of talking we will arrive at yet another point of view.

ASP: I enjoy

thinking about this arena or space that you are talking about; a background

space that we can access—in the case of these specific thinkers—only in second

hand fragments. We can’t see an original source but we know it exists. You

mentioned the advances in understanding the brain’s functions and how that

correlates to psychology. Going back to speculative realism where there is

something outside the subjective realm Kant described, I have a question about the

background. Where is it? Is it in the biochemical synaptic architecture of our

brains? Or, is it in the patriarchal social structures that we have endured and

respond to? Where would you place it?

HB: That is a

great question. My use of the background is as a very expansive term. It covers

a lot of layers. At the bottom most layer, it resides in very specific hardwiring

of neurophysical events.

ASP: Would you

say that it is found in the old brain? The base of the brain is the oldest part

of and where the most animalistic, involuntary thought processes take place.

HB: Yes,

absolutely. I went to a great lecture by Scott Soames. He is trained both in

neuropsychology and Freudian Analysis. He talked how our sense of being in the

world is located in these very primitive brain centers. Without these, we don’t

really have a sense of our agency in the world. Jaak Pankseep is a

neuropsychologist who has mapped out certain areas of the brain. There are

certain fundamental affects that associated with the layer on top of this

ancient brain. So the ancient brain in basically, “I’m here.” In the next layer

are affects that we share with other mammals.

Then as a social species we have a third layer from which social interactions

and relationships and language are controlled. This third layer is what I mean

by the psychosocial layer of thinking in which human society is structured.

ASP: I’m very

interested the idea of the speech act. The ability to make a word, to say,

“that.” A baby will point at something when she identifies with something.

Pointing is the first impulse behind wanting to name it. In a sense, you

project something of yourself on to the object. It has meaning for you. There

is something very moving for me about that process. Word formation has an

emotional component because I feel it connects back to being able to understand

and defend your own identity.

HB: No question.

I’m very glad you said that it is moving, because I agree. It’s our emotions

that actually impel us to go out, connect with other people, talk, and become

the basis for cognition. You see this in “Descartes’ Error,” by Damasio. Its

not as if emotion and thought are separate; there is a very complex interaction

between them. Something about how complex that is to happen is very moving to

me because the project of modernism—and I think we are still in a modernist

phase—is to try to uncover this manifold background. I think Marx, Freud, and

all the thinkers of doubt, said, “We have this surface, but there is more to it

than that.” Painting is in a very good position to talk about this phenomenon,

not only the context of speech acts, but also about their long historical

background. There is a way in which our social interactions have had this long,

historical winnowing of certain processes that lead us to where we are now. They

have been shaped by history. It’s very interesting to look at painting’s long

history as a parallel. When I make a painting its almost as if I am trying to

present a map of the subject state that I have that actually brought me to

create that painting and this is what I have to offer to other people. I am

making the assumption that because you also have subjective states that are

somehow congruent with mine, this will actually have some meaning for you.

ASP: I respond to

your work, I’m interested in it; I want to know more. I would say, you are

succeeding.

HB: Thank you.

(Both laugh) Good. We all have this intuitive assumption that there is going to

be a sufficient degree of congruency; we will be able to make representations

that we will be able universally understood. I am noticing, for example,

certain things that come up in your work; the sphere in Diving Bell and Pitch has

this wonderful map-like quality to it. Is there something you are trying to

work your way out of in these paintings or trying to move beyond?

ASP: As I move

from one piece to the next, I think about how Kant described the sublime as

something larger than us. I associate that with being overwhelmed by anxiety. I

am anxious almost all the time (laughs.) What I am looking for is some way to

address that, give it context and resolve it. The things that make me uneasy

are important yet somehow unapproachable. They are beyond the horizon. I know

something about them, but I don’t know enough to know what the proper, safe, interesting

or even funny response should be. The idea of inserting the monkey wrench is one

way—in the face of this uneasiness— of being able to find the resources to be

clear headed, calm and come up with a way regain direction.

HB: So throwing

in the monkey wrench is a way for you to break out of the stability and be comfortable

with the instability and in that way you are managing that aspect of trying to

hold on to control.

ASP: For me, it’s

working to accept the situation. The phrase “going with the flow” comes to

mind. If you are skiing down a steep hill and you feeling like you are not in

control, then go straight down. Don’t fight the forces and try to do any

switchbacks. Its not relinquishing or giving up the struggle so much as

dwelling with it, learning from it and saying, “Oh, there’s a new word here.”

These paintings aren’t part of a series, so to speak, but I do find that there

is a dialogue between them especially because in a concrete way I will do a

pour on one painting and press another painting on the same pool of paint. The

mirror image of the shape will appear on the second painting. So, in some ways they make each other. I am motivated

to be as expansive as possible about the process. I want to find relief. I

change my mind a lot and I know a couple of things, but then I don’t know a lot

(laughs.)

HB: Right. Your

story about going straight down the hill made me very anxious. I’m not sure

that’s the way I’d go about it.

ASP: It’s about

accepting that the moment is about speed. Finding that the momentum is with you

and through that you can regain control.

Working from the old brain up.

About the Artists:

Anne Sherwood Pundyk is a painter and writer

based in New York City and Mattituck on the North Fork of Long Island. Just as

abstraction has transformed representation in modern and contemporary painting,

performance poses its own problem to the medium. Pundyk’s new work is a

response to the question of how to paint the theatre of agency. Her painting, "The Revolution Will Be Painted," is on view through February 3, 2017 at The Schelfaudt Gallery, Bridgeport University, CT, as part of the group exhibition, "Reality of Abstraction,"

Hovey Brock

is a Brooklyn-based artist and educator who practice painting and social

engagement. His current research focuses on consciousness and image theory. He

also writes for the Brooklyn Rail and other publications.